Andrew Downes: A Life of Ill Health

Follow Cynthia Downes on Instagram to keep up-to-date with her blog posts.

Andrew Downes outside Hagley Hall where his 6th Symphony was to be performed as part of his 70th Birthday celebrations, raising money for Stoke Mandeville Spinal Research. #andrewdownes70

An account by his wife and publisher, Cynthia Downes, posted on June 1st, 2020

I remember my mum telling me when I was quite young, long before I met Andrew, that all great composers have to suffer. This was certainly true where Andrew Downes was concerned.

When he was 12 years old, while Andrew was on a camping holiday with his family in the South of France, he was struck down with pain in his left hip one morning and couldn't move. The painful condition plagued him throughout his teens and wasn't diagnosed till he was eighteen, when he was told by a consultant that he had ankylosing spondylitis, an extremely painful arthritic disease which slowly creeps up the backbone, destroying the cartilage between the vertebrae and gradually fusing the spinal column together, leaving it rigid, curved and brittle.

In his teens and twenties Andrew walked without flexibilty, but had a very straight back, which lasted until his 30s. The following 3 photos illustrate his upright posture:

Left to right: Andrew Downes, his Grandmother, Flora, Father Frank and Mother Iris

Andrew Downes, countertenor at St John's College, Cambridge from 1969-1972, front row of Choral Scholars (behind the choir boys), 4th from right.

Andrew had a beautiful Countertenor voice, but sadly had to give up his singing career, which included singing the role of David in Handel's Saul in the Goettingen Festival in Germany alongside Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau singing the role of Saul. You can hear Andrew singing in a recital in 1975 here:

dd

dd

Andrew Downes' Wedding to Cynthia Downes, 1975

Then, over the years Andrew's spine gradually curved over like a walking stick, causing constant, immense pain and stiffness. The developing curvature can be seen in the photo below and in the photo in the next article, which appeared in the Solihull Select magazine in 1995.

Andrew Downes talking to Betty Boothroyd after his Fanfare for Madame Speaker had been premiered at her Installation as Chancellor of the Open University at Symphony Hall, Birmingham

Andrew never complained, and led a full and active life, starting up Composition Studies and becoming Head of the School of Composition and Creative Studies at Royal Birmingham Conservatoire. After his early retirement on health grounds (after 30 highly successful years at Birmingham Conservatoire), he was awarded an Emeritus Professorship for carrying out his work at the Conservatoire 'with distinction'. At the same time he carried on composing throughout his life, no matter what. Performances of his music continue to take place all over the world. I accompanied Andrew on many exciting trips abroad for performances of his music, while he was still well enough to travel. Andrew always led as normal a life as possible. We had countless happy times and unforgettable experiences, which I describe in my other Blog posts.

On the morning of October 8th 2009, however, when Andrew, then aged 59, got up at 5am and went into our music room to turn our computer on, his left hip gave way. He fell, and I think our sellotape dispenser fell on his head: on hearing a crash, I rushed in to our music room and found him unconscious on the floor. I dialled 999. The ambulance drivers, not knowing that he was normally a person who would never scream out in pain, made him get up and walk down the stairs. The doctors in A&E at Russells Hall hospital diagnosed a urinary tract infection. Our daughter Paula and her husband David came up from Hertfordshire to be with us and help us through the long wait for treatment (Anna, our older daughter, was herself in hospital at the time, having undergone a hysterectomy). Andrew didn't get an x-ray until 9pm that day and then had to wait till the next morning for an MRI scan, which finally revealed his back was broken in two. It took all of the the day of October 9th for the medics to get him to the Birmingham Royal Orthopaedic Hospital and organise for a surgeon to mend his back. Mr Mel Grainger, a brilliant surgeon, came in that Friday evening and operated on Andrew between 9pm and 3am. Mr Grainger said if he could have done the operation within 24 hours of the accident, he could have guaranteed Andrew would walk again, but he warned us that now our lives would radically change. He was very angry that we had been kept waiting so long in A&E/EAU.

After a week in the Royal Orthopaedic hospital, Andrew was transferred by ambulance to the Spinal Injuries unit at Stoke Mandeville hospital. The journey caused him to lose so much blood that he had to have a transfusion of 3 pints of blood. The care in the unit was excellent. Andrew spent 9 months there, gradually healing and learning how to live as a paraplegic. He never complained and was always cheerful and very funny. The nurses always put depressed patients next to him, because he always cheered them up.

(I spent half of the week there and half at home, seeing to Lynwood Music orders and organising adaptations to our house. Our daughter Anna approached Irwin Mitchell Solicitors, who immediately pursued a case of clinical negligence and at the same time gave us immense help and advice on the house adaptations and the challenges we had to face.)

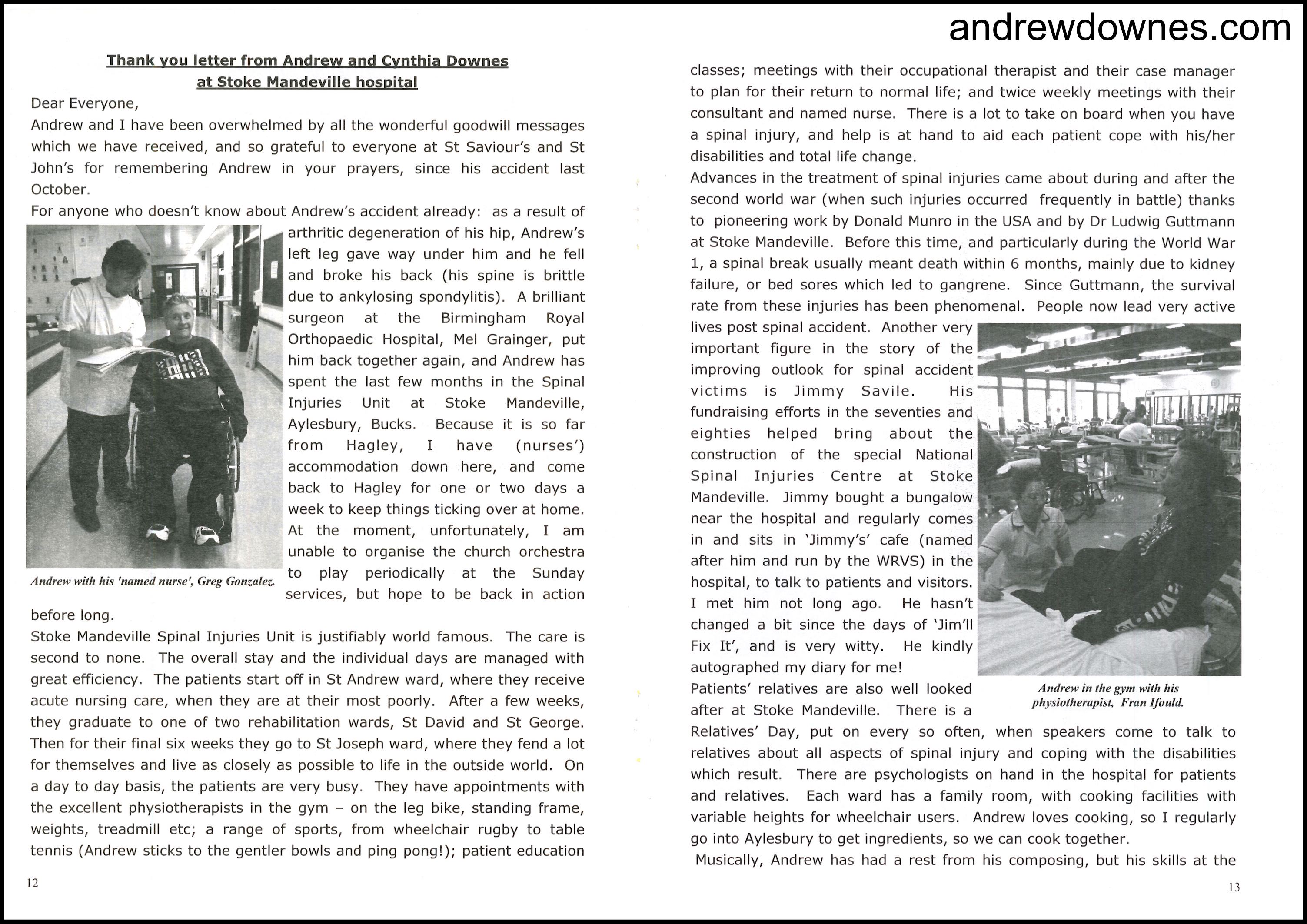

I wrote an article on our Stoke Mandeville experiences for our local Parish Magazine. It can be viewed here:

Andrew and I gingerly left hospital on June 23rd 2010, having been given training in transfers in and out of the car and all kinds of preparation for our new life.

Andrew didn't compose during his 9 month stay in Stoke Mandeville, but it was all going on in his head... When he got home he quickly completed his Horn Concerto for Czech hornist Ondrej Vrabec with Anna's Central England Ensemble. We performed the work in Birmingham Town Hall in 2012.

Life got

easier when we got a wheelchair accessible vehicle with an automatic

ramp (leased from 'Motability'), which we used to drive

around the Midlands to take flyers for our concerts.

Andrew's bone fragility problems were not over, however. He suffered 3 leg breaks in wheelchair accidents. His scans revealed osteoporosis and so he had to take calcium every day and the very strong drug, Risendrate, once a week.

For his pain, now mainly caused by spasms, Andrew was taking gabapentin and ibuprofen regularly, which in themselves caused problems. He started to fall asleep throughout the day and caused himself bad leg burns when he fell asleep and knocked over a cup of boiling hot coffee. Then in 2015 he suffered a brain haemorrhage, caused by the ibuprofen. Russells Hall hospital Stroke Unit knew what they were doing in this case and brought him through in a matter of days. Having completely lost his speech, Andrew recovered within a short time. He was discharged by a very nice consultant at the hospital after a month. Then, after 3 months, we received a letter saying his MRI scan results had come through and showed he was suffering from incurable cerebral amyloid angiopathy, which would cause more strokes, dementia and death within 10 years. Andrew refused to believe this. I wondered if they had sent this letter to the wrong person. A year after the stroke we had another letter, this time from Bromsgrove Health Authority, saying they were now happy to discharge him. Our GPs never mentioned it. For 7 years, Andrew did not suffer from those symptoms. One thing that letter taught me was to make the most of each and every day we had together.

At Christmas 2016 Andrew

contracted a chest infection. By New Year, he got so bad that I dialled

999. The paramedics, having carried out various tests, said Andrew was

ticking all the boxes for sepsis and needed to go to hospital. This was

the very worst time of the year. The hospital was packed to the rafters

with patients. It reminded me of the pictures of Florence Nightingale in

the Crimean war. The hospital said there was no room for visitors, so

our daughter Anna had to go home. I insisted on staying, because

Andrew needed me as his carer. I stayed all night tending to his needs

and getting some sleep on an uncomfortable plastic chair. Andrew slept

in his wheelchair. At 4am Andrew, still in his wheelchair, was put on a

drip of strong antibiotics, which zapped the infection. We went to the

next stage, the Emergency Assessment Unit, at about 5am, but Andrew was

discharged from there mid morning. I was very impressed at how the A&E

had gradually dispersed all their overnight patients to different wards

or home. We were very relieved that for us our journey out of EAU was

homeward.

In December 2018, Andrew again became

very unwell. He wasn't himself at all and got so bad that he couldn't

use the TV remote, his mobile phone or the computer. It was again a bad

time for hospitals, with ambulances queuing outside A&Es. Knowing

Andrew could not survive that, I waited to phone the surgery for an urgent

appointment with the GP next day. The doctor immediately booked

Andrew a bed in a very nice assessment ward in Russell's Hall Hospital. We had avoided A&E! But the hospital couldn't help, despite numerous

tests. After 5 weeks, we found a nursing home for Andrew, because we had

no hoist at home and Andrew was now too weak to use his standing turner

to get into bed. After another week, Andrew coughed up blood at the

nursing home. He was taken by ambulance to the Royal Worcester hospital, where an

endoscopy revealed he had non-alcoholic sclerosis of the liver. The

doctors didn't hold out much hope for him and in a conversation with

Anna, Paula (who had driven up from Cambridge) and myself, asked us to

sign a 'Do not resuscitate' form. Andrew spent 5 days in their High

Care unit. All of a sudden, on arriving at the hospital on the morning of the 6th day, I

discovered he was in the Discharge ward. A miracle drug, Rifaximin,

which stops the toxins given off by sclerotic liver from causing brain

damage, saved his life. Andrew quickly started to recover his brain

function and was able to compose just as brilliantly for 4 more years.

The woes didn't end there, unfortunately. Just after Easter in 2019, we realised we had forgotten Andrew's ramp

when we visited Anna and family in Kidderminster. We therefore took the

anti-tips off the back of his wheelchair to get him over Anna's

doorstep. We were so busy talking, that none of us remembered to put the

anti-tips back. When he flipped his front wheels over Anna's bathroom

door threshold, he tipped backwards and broke his C7 vertebra in 2. For

3

weeks no medics in our area would recognise the need for a neck x-ray. Our daughter Anna arranged for us to see the first available private

specialist, who happened to be in Coventry (30 miles from our home in

Hagley. Our son-in-law Mike drove us there). The specialist, Professor Shad, took about

12 xrays, didn't like what he saw, and sent us over the road to Coventry University hospital, where Andrew spent the next

5 weeks. The hospital was caring, clean and efficient. Mr Sneath, the brilliant bone specialist there, decided not to operate, because

Andrew's bones

were too brittle, but instead made him a neck and thorax brace. I

commuted from home to the hospital, taking 6 trains and 2 taxis

altogether each day, but I didn't mind the travelling, knowing

Andrew was in safe hands.

Andrew in his neckbrace in Coventry Univeristy Hospital

For Andrew's 70th Birthday yesr our daughters organised numerous celebratory events: #andrewdownes70, raising money for Stoke Mandeville Spinal Research and for Anna's 'Music for Sanctuary' charity for the homeless. In February Paula sang Andrew's Celtic Rhapsody with Anna's Central England Ensemble, conducted by Anthony Bradbury, in which I also played, in the Elgar Concert Hall of Birmingham University. Andrew came to the concert with our son-in-law, Mike, and our 2 grandsons, and loved it. During the coronavirus lockdown a number of Andrew's works were performed online.

In 2022 Andrew's health further deteriorated. His spasms had become more severe, and the doctor prescribed pregabalin. in the Autumn of that year, he started having bouts of deep sleep from which we couldn't wake him. On a couple of occasions, I thought he had suffered a massive stroke, and called 999. It got to the point where I couldn't go out and leave him. in spite of all this, he remained cheerful and lovely company, and he continued to compose brilliantly, right up to Christmas Eve. His last work was his Sonata for Bassoon and Piano, which he had almost finished. Our daughter Paula completed this work early in 2023 by adding a coda based on the ending of Andrew's Song of the Prairies.

On Christmas Day morning, Andrew went into a comatose sleep again. I called the paramedics, who discovered his oxygen and sodium levels were extremely low. They took him to Worcester hospital. Thankfully, Andrew didn't have to wait outside in the ambulance, but he had to join the rows of stretchers along the corridors, each row being looked after by a paramedic. He spent 50 hours in the A&E, twice in the overflow ward, and once in A&E High Care (which turned out to be a Covid ward as well). He was then transferred to 2 assessment wards, the second a 'short stay' ward. We were not allowed to visit 'short stay' for 3 days, because there were flu and covid outbreaks on the ward. On the 4th day I got a call from the nurses to say Andrew was 'very poorly' and we could spend as long as we liked with him. Our daughter Anna knew he was going to die, because she had studied the prognosis for end-stage non- alcoholic cirrhosis of the liver, which had been caused by all the drugs which Andrew had been given for his pain. He slipped further into his coma and passed away at about 5am on the morning of January 2nd.

As throughout his life, Andrew suffered in silence, but was mercifully asleep for most of his final days. The doctors tried everything to make him better, but Andrew's condition failed to respond to their treatments. He was looked after by some very kind nurses, for which I will always be grateful.

The outpouring of grief when Anna and Paula announced Andrew's death was overwhelming.

Anna and Paula organised Andrew's funeral, with lots of music by Andrew. Anna gave a beautiful eulogy, and Paula sang Andrew's heartrending song The Walk from his cycle Lost Love, with her husband David Trippett (piano) and our friend Jo Jefferis (cello). Both daughters have continued to keep Andrew's amazing legacy going with performances and recordings of Andrew's music.

As part of her Music and Conversation series, Paula created an immensely moving Podcast episode, entitled 'Remembering Andrew Downes', with her own special memories of her wonderful relationship with her Dad:

Follow Cynthia Downes on Instagram to keep up-to-date with her blog posts.

ddd

ddd

If you have performed in any of Andrew Downes' works or come to listen, please share your experiences in the Premieres Blog! Also see what others have said. Thank you so much for your contribution.